Interview: COBO future-proofs its components business

30 October 2024

Italy’s COBO S.p.A. is investing in its export markets and making a pitch on its capabilities as a systems integrator. Murray Pollok spoke to the company’s Stefano Scapin at its HQ near Brescia, Italy.

If you want to export you have to be out and about. That is certainly true of Stefano Scapin, chief business development officer for Asia Pacific at COBO S.p.A., the Italian supplier of off-highway components and technology.

Based in Hong Kong and Guangzhou for the past 8 years, Scapin navigates around Asia working on the company’s export business, and he and his colleagues have been successful: sales outside Italy now represent around three quarters of its €330 million annual revenues.

Stefano Scapin, chief business development officer for Asia Pacific at COBO S.p.A., pictured at the company’s Italian HQ. (Photo: KHL)

Stefano Scapin, chief business development officer for Asia Pacific at COBO S.p.A., pictured at the company’s Italian HQ. (Photo: KHL)

India has been a frequent destination recently, because COBO is soon to establish its 12th assembly and technology centre, close to New Delhi, from where it will serve the growing off-highway sector in India, mainly in construction equipment.

“It is one of the most important strategic and fastest growing business areas for us”, says Scapin, speaking to IRN at COBO’s head office in Leno, south of Brescia in northern Italy, during a short trip to Europe, “When we first traveled there, we had no people and only a couple of hundred thousand euros turnover, but today we are touching €7 million in India.”

COBO already employs around 15 people in the country, with around 10 more to be added, and is working with close to 50 OEMs, both local and international businesses.

Localisation strategy

The Indian plant is part of a strategy of globalisation that the company – which was established in 1949 by two car electricians - has followed for several decades. That has included numerous acquisitions, notably of wiring specialist CIAM in 2000 and safety control business 3B6 in 2006.

It now boasts facilities in the USA, China (since 2005), Romania and elsewhere, although its Italian facilities remain a key part of the company’s business. North America accounts for between 10% and 15% of its business and Asia Pacific is a similar level.

Scapin makes the point that its global centres – there are around 90 staff in both the US and Romania and 25 in China – are not solely focused on product manufacturing, but rather local service; “In particular, we have to make sure that we can offer this localisation, not of the product, but of the service. The key for localisation is not about cost, but service.”

The Indian plant is a good illustration. “We are moving towards having a local assembly plant and more engineering, because we are doing software in India for the applications with Indian customers, and for the applications of Asia Pacific customers”, he says. India will also be used to test and debug products developed and made in COBO’s seven Italian plants.

“The goal of the facility in India will be to better serve the local market and then to improve the time to market. And when we say localization, it is not just localized assembly, it’s localized projects top-down.

Quality control staff examining the printed circuit boards which are made at the Leno HQ in Italy. (Photo: KHL)

Quality control staff examining the printed circuit boards which are made at the Leno HQ in Italy. (Photo: KHL)

“We need to have engineers there who are able to understand the application, support the sales to win the business, write the specification, develop the software, then install, calibrate and validate.”

Helping it do that is an almost bewildering range of products, from lighting, controllers, switches, steering columns and armrests to infotainment screens, wiring harnesses, telematics systems and sensors. There are 32 product lines and around 70,000 part numbers.

It is no surprise that vertical integration is a characteristic of the business. It makes it own printed circuit boards (PCBs) in Italy - a fourth PCB production line was under construction during IRN’s visit – and steering columns are another example; “Our steering column kit assembly is kit of sub-components that we design, develop, manufacture and put together.

“We are not buying parts and assembling them, but we are actually making the rocker switches, the lever combination switch, the wheel, the plastics, the armrest, the keys switch, and the display and the software. This comes to the OEM as a plug and play solution. And it’s very popular.”

System integration

This systems integrator capacity is a key sales pitch when it comes to COBO winning business, especially with smaller OEMs.

“When we work at that early stage with the OEMs, we design the electrical schematic, and we have a great opportunity because we have such a wide product portfolio”, explains Scapin, “We can have the electrical schematic design and of course promote all the electrical peripherals that are linked to the schematic.

“Think about lights, about switches, clusters, controllers and so on that eventually are linked together with the software. We have many OEMs that are very small, but are coming to us as an expert, as a system integrator. And we have an opportunity to provide a big scope of supply, sometimes with low volumes. But the value for each of these machines can be high.”

And when working with bigger OEMs, the scope of supply may be less, but the volumes higher.

Example of the largest, 12 inch wide displays made by COBO. (Image: COBO)

Example of the largest, 12 inch wide displays made by COBO. (Image: COBO)

“We are actually really looking to find a relationship with the engineering of the OEMs, because the main target for us is not the purchasing department”, he says, “The aim is to work with the technology people, and then build up a relationship to understand what they’re working on at that very early stage, possibly the concept stage”.

Scapin says 20% of COBO’s 1500 employees work in R&D, and not only in Italy; “We are doing R&D also in the subsidiaries. So, when we develop a new platform, a new product, typically the electronic design, the firmware design is made here in this technical office [in Italy].

“And then the engineers located across the global subsidiaries typically focus more on the application for the customers.” COBO will typically invest around 10% of revenues in R&D each year.

As a global player, with 4000 clients in agricultural and construction markets, it is also at the forefront of determining how the controls of the future will be designed, including displays and infotainment systems.

“Now everything is moving towards more sophisticated graphics, with 32 bit microprocessors and 3D graphics animations”, he says. In fact, the one exception to its off-highway focus is its business with high-end automotive and motorbike brands, where it is supplying instrument panels for clients including Ducati, Lamborghini, KTM and Pagani.

The involvement with high-end automotive brands is helping it develop its technology, for example in its HMI (human machine interface) displays; “When we entered that segment, the first project was with a motorcycle manufacturer, and we have been producing our first TFT [thin film transistor] displays. For example, five or six years ago most of the motorbike screens were just 4.3 inches, no bigger than five, then to seven. Now we are seeing even bigger than seven inches.”

Its largest display now measures 12 inches, and there will be more applications where such displays, instead of being in front or on the steering wheel, will be installed on pillars vertically.

“Today we are working on wider displays, different formats of display, 3D graphics”, Scapin continues, “We also have a department of advanced engineering. We are about seven people there that are working on assisted and autonomous driving, electrification, and new farm management systems.”

He thinks voice control will become more important in the off-highway market; “I’m very confident that it will be very useful in in mobile machinery. We are moving towards autonomous driving or self-assisted driving, and then voice control.”

Autonomous driving?

Autonomous driving will come sooner in agriculture than construction, he thinks, partly because the farming environment can be a safer and more predictable environment. “Construction might still be a tricky part. I would still watch automotive before saying construction will be implemented.”

There are other areas where innovation is becoming key, such as keyless entry systems for machines.

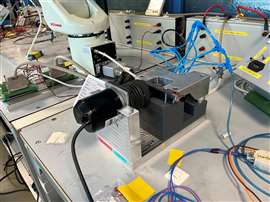

Mechanical testing of a component underway at COBO’s Italian HQ. (Photo: KHL)

Mechanical testing of a component underway at COBO’s Italian HQ. (Photo: KHL)

“If you look at cars, they will have a key fob to open the doors, blink the lights, and so on. But we have done something more here because it is not just the fact that you don’t have the mechanical key. In the context of mobile machinery, one machine can be operated by different users, different operators, and each operator has one ID.

“If the machine is fully electronic, that ID will be recognized not just to open, but also to configure all the settings: language, colour of the display, position of the seat, the inclination of the steering wheel, and so on…We already have some clients where we are into the pre-series stage, and we are getting into the mass production by the end of this year.” This will be for both agriculture and construction applications.

COBO has been particularly active in the aerial work platform sector, in terms of boom sensors, and telematics systems and keyless technology. It is also looking at wider use of sensors, radar and other technologies for safety applications, such as anti-collision and anti-entrapment.

“I think technology will always be a stimulus to create new opportunities. And sometimes we know that people are thinking - will it be competitive? Will it be a cost? But technology is also a way to differentiate. If you’re able to present the right product with the right technology, you might create a new opportunity alongside a norm or a regulation that is always being interpreted.”

In aerial platforms, for example, he thinks sensors can help promote safety because it can introduce ‘intelligent’ solutions; “they say the MEWP operator should wear a harness, and so on. But there must be something more intelligent…our sensors and controls are the brain of the machine and we have that capability to advocate, to promote zero incidents.”

He likens to shift to zero incidents to the Japanese culture of zero defects in manufacturing; “We cannot accept that people are dying or getting injured because of accidents at work, right?...I think technologies are available to minimize or to implement a zero incident culture. Radar, ultrasonic, Lidar, and in some cases, cameras, yes. There is technology available and already deployed in the market.”

Supply chain disruption

Of course, COBO operates in a supply chain environment that has seen enormous disruption in recent years, with the pandemic, ongoing war in Europe, and the rise of geopolitical tensions and the possibility of more import tariffs in the future. It has led to more and more discussion of localised chains.

“If it does not happen yet it will probably be happening very soon, given the coalitions that are forming on a global level, even the geopolitical aspects”, he says, “So de-globalization is already there. To be successful on a global scale, you have to be present on different continents.

“In our context it might not be sustainable to set up manufacturing plants in Mexico, because we are already present in the US, but you cannot think of working with Chinese OEMs if you are not in China.”

A display for an agricultural tractor. Agriculture and construction equipment OEMs are COBO’s two biggest customer groups. (Photo: KHL)

A display for an agricultural tractor. Agriculture and construction equipment OEMs are COBO’s two biggest customer groups. (Photo: KHL)

The other current theme is a market softening, particularly in Europe, after several busy years. “In Europe for sure there is a double-digit decline, and sometimes the double digit may start with a 2.” That comes after several years of post-pandemic growth; “some of the demand was just unreal because of the shortages, because the ordering was higher than the real demand.”

Diversification of its customer segments helps here, with around 35% generated by customers in agricultural machinery, 25% in construction, 10% for automotive/motorbikes, and the remaining 30% for clients in lifting equipment and niche areas such as road sweepers and ground support equipment.

And the slowdown this year should be seen in the context of pretty dramatic growth, with the €330 million last year representing 50% growth over the €220 million in 2019.

So, a lower level of business this year, but not a crisis; “I think what really counts is when you have these ups and downs, you always need to concentrate on new clients, new projects. That is what guarantees the sustainability of the business.”

And it explains why Scapin and his colleagues are constantly on the move.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM