5 reasons why construction suffers stubborn labour shortage in Europe

14 May 2024

Europe’s construction industry continues to suffer a labour imbalance, with almost half the occupations classified as being in shortage in the region belonging in the sector.

That’s according to the latest EURES report on labour shortages and surpluses published by the European Labour Authority earlier this month.

Employment in construction has gradually recovered since the 2008 financial crisis, after falling by three million workers in the European Union (EU) between 2008 and 2014. But it still stands below its 2008 peak of 15.3 million.

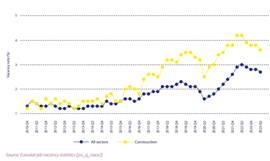

In the second quarter of 2023, the construction sector reported the fourth highest job vacancy rate of any sector in the EU. The JVR in construction has also increased at a higher pace than across all other sectors in the EU since 2016, according to the EURES report.

Vacancy rates for construction and all sectors in the EU27, Q4 2014 - Q2 2023 (Image: EURES report 2023)

Vacancy rates for construction and all sectors in the EU27, Q4 2014 - Q2 2023 (Image: EURES report 2023)

So what is behind construction’s labour imbalances in Europe? The EURES report examined five key factors. They were:

1) Age structure

As in many other parts of the world, the construction industry has started to face an acute problem with the number of people ‘ageing out’ of the sector. In Sweden, for example, it’s estimated that 10% of the construction workforce will retire by 2028, according to the report. In Belgium, 20,000 skilled workers are expected to retire by 2027.

Separately, the Cedefop Skills Forecast highlights that while there will only be a modest increase in employment in the occupation of 88,000 posts from 2022 until 2035, the net requirement will be much bigger, driven by the retirement of existing workers. It estimated that 4,127,000 people in Europe will leave the occupation over that time. That makes a net requirement of an additional 4,215,000 people in the sector between 2022 and 2035.

2) Attractiveness of the sector

Traditionally, working conditions in the construction sector have put off would-be entrants. Reasons cited, according to the EURES report, include physical demands, exposure to chemicals, repetitive movements involving tiring and panful positions, and often being required to work outside. It also noted that climate change could have an impact on this, with exposure to higher temperatures and more UV radiation. It acknowledged that working conditions in the sector is improving significantly, with higher wages, innovation that has made tasks easier to perform, and better health and safety practices.

Nonetheless, it referenced a 2023 report from the European Construction Industry Federation (FIEC) which noted that the construction industry’s image lags behind the improvements it has made. “There is little interest for young people to pursue a career in construction. Despite technical innovation, the sector’s representation in the public mind did not improve much and it continues to be unattractive,” it warned.

The EURES report suggested that high levels of subcontracting and self-employment also affect the attractiveness of the sector.

But it did note that a measure of job quality developed by Eurofound (2022) found that workers involved in the construction of buildings are less subject to strain than those in other sectors.

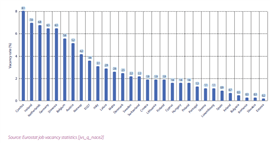

Job vacancy rates in construction by country, EU27, Iceland, and Switzerland, Q2 2023 (Image: EURES report 2023)

Job vacancy rates in construction by country, EU27, Iceland, and Switzerland, Q2 2023 (Image: EURES report 2023)

3) Structure of employment

The EURES report noted that the structure of employment in the sector, with multiple tiers of subcontracting, means high levels of self-employment and temporary employment, which leads to fragmentation and makes it difficult to negotiate or coordinate the introduction of improved working conditions and pay. A relatively high share of employment in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) potentially also means that companies are less able to obtain information on how to acquire the labour they require, the report suggested.

4) Not making the most of available labour supply

The construction industry fails to make the most of available sources of labour, the report noted. In particular, it highlighted the lack of women in the sector. In 2008, female employment was 8.4% of overall employment in construction. By 2022, that figure had increased by just two percentage points to 10.4%. By contrast, women account for 46.2% across all sectors. Even the country with the highest level of female construction employment, Luxembourg, only has a 15.6% share of female employment. The EURES report referenced another report from 2020 called Women Can Build, which suggested that women may be expected to behave in a certain way within a construction environment to be accepted, while jobs that require strength are considered ‘masculine’, there is a lack of work-life balance that does not suit women with caring responsibilities, and PPE is often not designed with women in mind.

Separately, the EURES report noted that some countries have a “degree of dependence” on workers from other countries. European administrative data, for example, shows that there were 855,650 ‘posted’ workers across Europe in 2021, who were working in construction outside of their home country. Germany was the main recipient country.

5) Availability of skills and changing skills requirements

The skills that the construction sector requires are likely to change as a result of the green and digital transitions, the report noted. The European Green Deal is expected to have a “substantial” effect on construction sector employment because of the demand to renovate existing building stock and cut the sector’s carbon footprint. The European Commission aims to at least double renovation rates over the next 10 years, but only 1% of buildings undergo energy efficient renovation every year currently.

The EURES report noted that EU climate change policies will lead to an estimated net increase of 204,000 jobs over the 2019 to 2030 period but questioned whether this level of employment could be realised given the difficulty the sector already faces recruiting labour. It suggested that technology had the potential to reduce the labour intensity of production at the same time as increasing attractiveness to would-be workers, citing tolls like BIM, drones, smart sensors, 3D printing and mobile technology. Take-up in the sector so far has been modest though, it noted.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM